Understanding AWE: Can a Virtual Journey, Inspired by

the Overview Effect, Lead to an Increased Sense of Interconnectedness?

Immersive

technology, such as virtual reality, provides us with novel opportunities to

create and explore affective experiences with a transformative potential

mediated through awe. The profound emotion of awe, that is experienced in

response to witnessing vastness and creates the need for accommodation that can

lead to restructuring of one's worldview and an increased feeling of

connectedness. An iconic example of the powers of awe is observed in astronauts

who develop instant social consciousness and strong pro-environmental values in

response to the overwhelming beauty of Earth observed from space. Here on

Earth, awe can also be experienced in response to observing vast natural

phenomenon or even sometimes in response to some forms of art, presenting vast

beauty to its audience. Can virtual reality provide a new powerful tool for

reliably inducing such experiences? What are some unique potentials of this

emerging medium? This paper describes the evaluation of an immersive

installation “AWE”—Awe-inspiring Wellness Environment. The results

indicate that the experience of being in “AWE” can elicit some

components of awe emotion and induce minor cognitive shifts in participant's

worldview similar to the Overview Effect, while this experience also has its

own attributes that might be unique to this specific medium. Comparing the

results of this exploratory study to other virtual environments designed to

elicit Overview Effect provides insights on the relationship between design

features and participant's experience. The qualitative results highlight the

importance of perceived safety, personal background and familiarity with the environment,

and the induction of a small visceral fear reaction as a part of the emotional

arc of the virtual journey—as some of the key contributers to the affective

experience of the immersive installation. Even though the observed components

of awe and a few indications of cognitive shift support the potential of

Virtual Reality as a transformative medium, many more iterations of the design

and research tools are required before we can achieve and fully explore a

profound awe-inspiring transformative experience mediated through immersive

technologies.

The

overwhelmingly beautiful sight of our Earth triggers a profound emotional

response in most astronauts, leading to a cognitive shift, making them realize

the global interconnectedness of all life and feel responsibility for the

future of our planet. This phenomenon was described by White

(2014) and termed the Overview Effect. This experience has

the attributes of self-transcendence and awe (Yaden

et al., 2016) and is a remarkable example of a transformative experience.

Besides the Overview Effect, there are other experiences that have similar

effect of evolving an individual as a changed person and promoting the feeling

of unity or interconnectedness. For instance, such experiences happen in the

context of interaction with nature (Williams

and Harvey, 2001; McDonald

et al., 2009; Tsaur

et al., 2013) or in religious or spiritual context (Keltner

and Haidt, 2003; Levin

and Steele, 2005), as well as mystical experiences, meditation, peak and

flow experiences during high task performance and several other contexts (Yaden

et al., 2017). The emotion of awe is often at the core of

these experiences (Yaden

et al., 2017; Chirico

and Yaden, 2018). Even though the terms “transformative,” “transcedent,”

and “awe-inspiring” experiences are not interchangeable, there is a large

overlap between the phenomena they are describing. For the purpose of the

project described in this paper, as we were aiming for the experience that is

laying anywhere within the cluster of these phenomena, we will be discussing

them together, without drawing a careful distinction between the terms.

Besides

being an enjoyable experience (Shiota

et al., 2011), such phenomena can have short and long-term positive

outcomes: leading to increased well-being (Ihle

et al., 2006; Suedfeld

et al., 2012; Krause

and Hayward, 2015), pro-social (Piff

et al., 2015; Prade

and Saroglou, 2016; Yang

et al., 2016; Stellar

et al., 2017, 2018),

and pro-environmental (White,

2014; Garan,

2015) attitudes, and even improved physical health (Stellar

et al., 2015). The feeling of interconnectedness can lead to the

development of social consciousness, which in turn would lead to pro-social

behavior (Schlitz

et al., 2010). However, despite all the benefits of transformative and

awe-inspiring experiences, they remain rare, inaccessible to some people (e.g.,

due to physical or economic reasons) and could be challenging to achieve at

will. Developing tools that could allow us to create environments that could

reliably invite such experiences to happen would greatly benefit the world on

both individual and societal levels. If we can facilitate the invitation of

transformative experiences even only half of the time, that already would make

such experiences much more accessible, and the tool allowing us to do that,

arguably, would be able to claim itself as a transformative medium.

Virtual

Reality (VR) technology with its controllability and ability to afford sense of

presence could provide us with a unique medium to design for and study

awe-inspiring experiences (Chirico

et al., 2016), making them more accessible to the public and researchers (Stepanova

et al., 2018). The potential of immersive technology to create applications

for positive change has been widely explored in different contexts, see reviews

in Kitson

et al. (2018a) and Riva

et al. (2016). Researchers explored the potential of VR to induce awe in

controlled lab conditions through using immersive videos (Chirico

et al., 2017) and virtual environments (Chirico

et al., 2018a), and were successfully able to elicit a self-reported awe

response in some of their participants. Quesnel

and Riecke (2018) and Gallagher

et al. (2015) have also used virtual experiences of a spaceflight and

evaluated its potential for inducing awe. Even though none of these studies

observed a transformative experience of a similar scale to the Overview Effect

in their participants, they still showed promising results indicating that VR,

as a medium, could successfully deliver experiences that can trigger profound

emotional responses such as awe.

However,

there is still little research on awe, as well as the Overview Effect and other

transformative experiences, that could inspire the design of a transformative

experience in VR. Moreover, a larger body of knowledge needs to be build about

the specific potential and affordances provided by VR for the design of

profound experiences, as well as an understanding of what would someone's

experience of going through such installation be like. As VR technology and

affective design are both relatively new fields, it is important to not only

bring in the understanding of how profound transformative experiences happen

outside of VR as a guidance for the design of the immersive experiences and

assessment of their effectiveness, but to also develop rich body of knowledge

of how such immersive installations are experienced by different individuals.

This study attempts to contribute to this developing body of knowledge by

describing and analyzing personal experiences of individuals going through an

immersive VR installation designed with a goal of awe elicitation and

invitation of a transformative experience. This understanding will be essential

for future assessment of VR technology as a more ecologically-valid approach to

conducting controlled lab studies of complex phenomena and for informing design

strategies, affordances and limitations for the development of profound

positive immersive experiences with transformative potential. VR technology can

not only allow us to “replicate” in a virtual world experiences that are poorly

accessible in real world, such as a spaceflight, but this medium also presents

its own unique opportunities for creating spaces and journeys that can invite a

transformative experience. For instance, technology in itself, with the

vastness of the data it can connect you to, can elicit awe (Bai

et al., 2017). Thus, it is reasonable to explore the virtual transformative

experiences as its own sub-cluster of transformative phenomena with its own

unique attributes and processes, but similar desired benefits such as an

increased feeling of interconnectedness, and the benefits for well-being and

pro-social and pro-environmental attitudes that could follow from it.

In

order to build this knowledge base about the transformative potential of VR and

the phenomenology of individual's experience in a VR installation, we need to

utilize our knowledge of profound transformative experiences to motivate the

design of VR installations and then study the experience it induces as its own

phenomenon. Using qualitative research methods allows us to develop an

understanding of how personal experience is unfolding and what the important

aspects of it are. Then, we can relate that understanding to the attributes of

the design and the desired outcome. Comparing the experience elicited by

different VR installations would provide deeper insights in how different

design elements, as well as the setting and participant's background might

correlate with particular aspects of the elicited experience. Additionally,

relating the personal experiences of participants to the design decisions will

help developers of transformative VR experiences validate their design

hypotheses and intuitions, as well as propose new direction for investigation.

To

achieve that, for this exploratory study we designed an immersive VR

installation “AWE”—Awe-inspiring Wellness Environment (description of

the development including the design hypotheses can be found in Quesnel

et al., 2018b)—that was inspired by the Overview Effect and other

awe-inspiring experiences in nature. This installation is not an attempt of a

virtual replication of an astronaut's experience, but rather an artistic

creation aiming at eliciting an experience that will have some similar outcomes

to the Overview Effect. The Overview Effect is described as a cognitive shift

that includes an experience of awe and feeling of connectedness to

the world, the people and nature (White,

2014; Yaden

et al., 2016; Stepanova

et al., 2018, 2019),

so these were the qualities of the experience that we were hoping to observe in

the immersants going through AWE. At the same time, giving the complexity of

the experiences of awe, self-transcendence, connection and the Overview Effect,

and the complexity of the conditions in which they may occur, at this stage we

couldn't directly test for an effect of singular aspect of the design of the

virtual experience on likelihood of the desired experience occurring. It

doesn't seem to be possible to isolate a singular aspect of the experience that

might be responsible for the desired experience in the immersants. Thus, in

order to form testable hypotheses about the relationship of the design and user

experience, we first need to develop a VR experience capable of eliciting the

feelings of awe, connectedness and cognitive shifts, related to the Overview

Effect; and then build a rich knowledge of the phenomenological experience of

that VR experience, from which new hypotheses can be derived.

In this

exploratory study we discuss the aspects of the experience that the

participants of “AWE” have described and relate their accounts to

the research on the Overview Effect and awe-inspiring experiences. This study

has two distinct goals: (1) evaluate the potential of the current research

prototype, “AWE,” for eliciting some of its desired effects that

have been associated with the Overview Effect; (2) develop a better

understanding of what are the important components of an individual's

experience of going through an affective VR installation designed for awe

elicitation, and how it can inform future system development and hypothesis

formation. To develop a better understanding of the different components of the

experience of a person going through an affective VR installation like “AWE” we

performed in-depth qualitative interviews with participants about their

experience. To evaluate the potential of our “AWE” experience to

elicit awe and ideally lead to a cognitive shift and increased

interconnectedness, besides comparing the thematic analyses of interviews to

existing qualitative research on awe and Overview Effect, we also implemented

two quantitative measures that could be used for assessing components of the

Overview Effect: occurrences of awe measured through goosebumps extending work

of Quesnel

and Riecke (2017) and Benedek

and Kaernbach (2011) and connectedness to nature measured through an

Implicit Association Test (IAT) used in Schultz

et al. (2004).

As this

is an exploratory and largely qualitative study, we were not testing any formal

scientific hypothesis. However, in the process of designing the “AWE” installation,

several design hypotheses were made as a part of the creation

process. Some of these design hypotheses are discussed in our paper describing

the development of “AWE” (Quesnel

et al., 2018b). Even though these hypotheses are not directly tested in

this study, they might have formed some expectations that we had prior to

collecting and analyzing the data, that were informed by these hypotheses.

Additionally, in a separate publication, we have also proposed design

guidelines for a virtual Overview Effect experience based on astronauts'

recollections of it and available research—Stepanova

et al. (2019). Those proposed guidelines have both informed the design of

the “AWE” and might have formed our expectations for the current

study. To minimize our bias in the analyses, we used phenomenological method

that attempts to suspend the researchers' expectations through the process of

epoché (a.k.a. “bracketing”) (Smith

and Osborn, 2004). After the analyses and reporting results, we turn back

to our expectations formed prior to the study and discuss the relation of the

results of this study to the guidelines discussed in Stepanova

et al. (2019) in the section 4 of this paper.

This

paper makes a contribution to several fields: to the field of the VR experience

design (esp. VR4Good—Virtual Reality for positive change) by identifying the

aspects of an affective experience of being in VR that can be supported with

thoughtful design of VR installation; to the field of transformative experience

design by describing possibility for inducing cognitive shifts in VR and how

they might occur; to the field of psychology describing possible methodological

approach for investigating awe, the feeling of connectedness and transformative

experiences, that might be difficult to access, like the Overview Effect.

2.1. Immersive Experience

and Physical Set-Up

Participants

were invited into the study room where there was a separate “tent” section for

the virtual experience and the preparation area with a table and a laptop,

where participants were signing the consent form and doing the IAT. The “tent”

was set up with a 305 × 305 × 211 cm gazebo, that was diagonally separated with

black curtains into the VR and the researcher (from where the equipment was

operated) areas. Inside the “tent” there was an office chair covered with a

blanket (to suggest the atmosphere of comfort) and some pillows on the floor

(to match the virtual environment (VE)); the outside of the “tent” was

decorated with fairy lights, that resemble starry night sky when viewed from

inside, which corresponds to the first stage of the VE (Figure

1). We set up the virtual experience inside the physical tent for two main

reasons. Firstly, to create an explicit entry into the experience space, that

would separate it from the formal study procedures space. As such, the stepping

into the tent was serving as a small ritual, that is proposed as a design

guideline for transcendent VR experiences (Kitson

et al., 2018b). Secondly, the tent was creating a semi-private environment

where participants knew that they were not being directly observed and can be

more immersed and expressive. We believed that these two conditions might be important

for inviting the opportunity of a transformative experience.

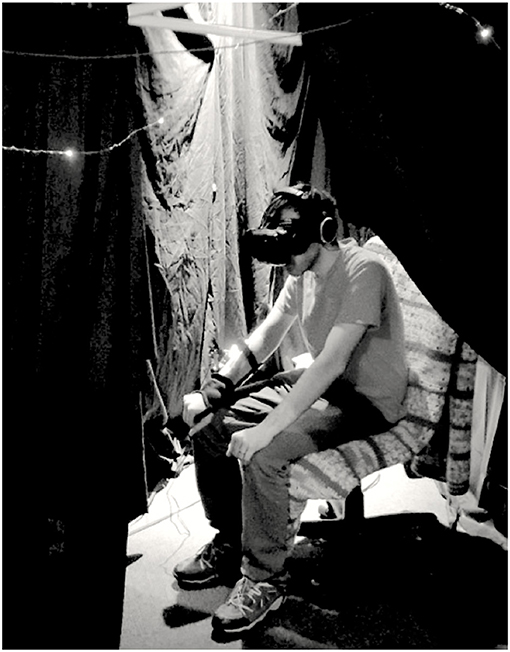

FIGURE 1

Figure

1. A participant inside the tent (with the open entrance curtain)

inside the “AWE” installation. The participant is seated on a

swivel chair, wearing an HTC Vive (2016 model, 2,160 × 1,200 total resolution,

1,080 × 1,200 per eye, 90 Hz refresh rate at 110° diagonal field of view) and

noise-canceling headphones on his head, and a goosebump camera on his right

hand. Written informed consent for the publication of this image was obtained

from the person depicted.

The

navigation interface used for locomotion was adapted from Swivel Chair (Nguyen-Vo,

2018), which uses the rotation and leaning of one's body for locomotion

through a virtual space. Participants were sitting on an office chair and

controlling their simulated self-motion by leaning in the direction they want

to go, with the amount of leaning determining the translation velocity in the

direction they were leaning. To rotate, participant turn around on the chair

that can spin 360°. The interface was calibrated for the individual's height.

The immersive

experience “AWE” (Quesnel

et al., 2018b) consisted of three environments: forest, lake and space

(see Figure

2 and a video of the latest prototype http://ispace.iat.sfu.ca/project/awe/).

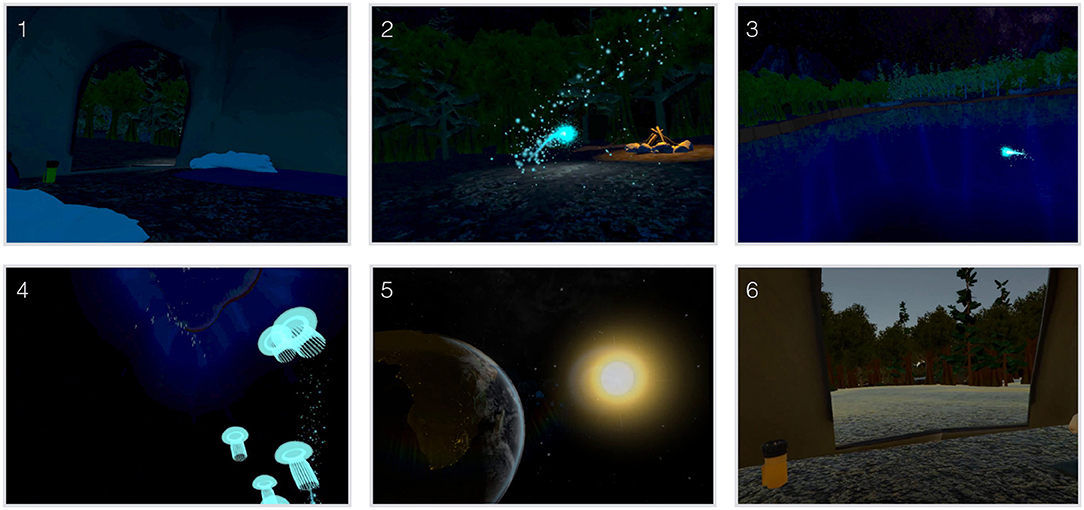

FIGURE 2

Figure

2. A summary of the virtual journey through “AWE.”. (1) The

immersant finds themselves in a tent at a campsite. (2) The

magical Sprite creature lures the immersant out of the tent to explore the

night forest. (3) Following the Sprite, immersant takes a leap

of faith into the lake, (4) where they descend down passing by

deep water creatures. (5) The bottom of the lake opens into

space where the Earth and Sun appear in a dramatic reveal. (6) After

orbiting around the Earth, the immersant finds themselves back in the campsite.

The

three stages of VE allowed for different amounts of active locomotion:

1. In the forest stage, immersants could freely explore the

environment along the horizontal plane;

2. in the lake, there is a limited range of movement in the

horizontal plane, but the overall vertical direction is directed by descending

within a virtual tube;

3. in space participants were taken on a pre-designed trajectory

with a limited range of movement.

2.2. Participants

As the

main contribution of this exploratory study relies on the phenomenological

analyses of the interviews, we were aiming for the recommended sample size

between 5 and 25 participants (Creswell,

1998). We used purporsive sampling method commonly used in exploratory

qualitative research in order to obtain rich descriptions from knowledgeable

participants (Palys,

2008). A total of 15 participants were recruited through a purposive

sampling method with the help of our partner organization—NGX Interactive, a

local company that creates interactive exhibits for culture industry.

Participants were recruited within the company's employees and clients and are

representing the community of professionals working in the field of culture

industry and technology. We specifically recruited participants who will be able

to provide us with well-informed feedback on the system and its potential to be

used in culture industry for facilitating shifts in worldviews, but they were

naive in terms of the specific details of this study. Additionally, even though

the experience with VR technology varied between participants, they had ample

experience with interactive technologies, and therefore would be able to go

beyond the initial “wow” response, that first time users of VR sometimes have.

We will be referring to participants as P#. Two participants (P07,P15) were

excluded from the analyses as they did not finish the experience due to

cybersickness, resulting in a final sample of 13 (7 females). The ethics

approval was granted by Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics (Study#:

2017s0269).

Throughout

the iterative development of the AWE experience we conducted a multitude of

smaller formative user tests with a range of participant populations to inform

the design of the AWE experience. While they generally confirm the results of

the current study, reporting them in any detail goes beyond the scope of the

current study and would not substantially alter the findings.

2.3. Procedure

After

signing the written informed consent form, participants were asked to enter the

tent and sit down on the swivel chair. The researcher explained the set-up

procedure and the navigation, handed the Head-Mounted Display (HMD, HTC Vive)

and the noise-canceling headphones to the participant and assisted with putting

the equipment on. Participants were instructed in case of a mild cybersickness

to close their eyes for a moment, and, if the feeling persists or is strong, to

notify the researcher and they would stop the experience. Next, the researcher

asked the participant to roll up their sleeve and put the goosebump camera

(explained in the following section) on their arm. Once confirmed that the

participant feels comfortable, the second researcher starts the virtual

experience, and the first researcher directs the participant through the

initial calibration process for the navigation, while second researcher starts

the recording of the goosebump camera. Then, the first researcher notifies the

participant that everything is now in order and leaves the tent leaving the

participant in privacy for the experience. After the virtual experience, the

first researcher returns to the tent to assist the participant with taking off

the equipment and sets up for the interview. After the interview, the

participant is directed out of the tent to complete the Implicit Association

Test (IAT) on a laptop (13-inch MacBook Pro). The participant's experience in

the VE was recorded through screen capture and the interviews were recorded

with a GoPro camera. The study took approximately 1 h.

2.4. Evaluation Methods

We have

used a combination of qualitative and quantitative measures to help us address

two goals: (1) understand the participant's phenomenological experience and (2)

to assess the potential of the AWE experience to create conditions in which an

awe-inspiring experience similar to the overview effect (or a degree of) may

occur. As the overview effect is described as a cognitive shift that starts

with an experience of awe and leads to the increased feeling of connection and

responsibility for Earth (White,

2014; Yaden

et al., 2016; Stepanova

et al., 2018, 2019),

we included measures of awe and connection with nature. We didn't include

specific measures of the responsibility for Earth at this stage, as first we

needed to establish that earlier stages of the desired transformative

experience can be achieved.

We used

interviews to collect qualitative data about the participants' phenomenological

experience of going through the VR installation. Additionally, we included two

quantitative measures to assess two components of the Overview Effect

experience: an implicit association test to assess the interconnectedness, and

a measure of piloerection (goose bumps) to assess the occurrences of awe. These

two quantitative measures were included as a methodological exploration in

preparation for future studies, that will use a randomized controlled

experimental design, less in-depth qualitative measures and a larger sample

size. Here, we hypothesized that we will observe a trend indicative of

correlation between the measure of awe and the measure of connectedness (higher

scores on the implicit association test will co-occur with higher number of

instances of piloerection), as in the Overview Effect they are described to

occur together.

2.4.1. Interviews

We

collected the qualitative data through either cued-recall debrief (Bentley

et al., 2005) or micro-phenomenological interviews (Petitmengin

et al., 2009). Both of these methods are designed to help participants get

re-immersed in the past experience and therefor to have more direct access to

different aspects of the experience reducing recall errors that could be

introduced with the use of retrospective measures (Henry

et al., 1994). To further minimize the recall errors caused by the delay

between the experience and the interview, each interview was administered immediately

after the virtual experience. We implemented both methods in order to assess

how they fit into the context of research of affective VR experiences and

evaluate what type of data they will be most effective at yielding. To keep the

study under an hour to avoid participant's fatigue, we used only one type of

interview with each participant: four participants (P02, P03, P04, P09) were

interviewed with micro-phenomenological and nine with cued-recall debrief

methods. Each interview was followed by a short set of general questions about

the experience. The type of the interview administered depended on the timeslot

(determined by the availability of the trained micro-phenomenological

interviewer). When signing up for the study, participants were not informed

about the relationship between the timeslots and interview methods. Each

interview took about 20–30 min.

2.4.1.1. Cued-recall debrief

After

the virtual experience, the researcher would help the participant to take off

the equipment, while the second researcher would turn around the monitor and

load the recording of participant's experience on the screen and set-up the

video camera. During cued-recall debrief (Bentley

et al., 2005) the participant watched the screen capture of the experience

together with the researcher and talked through what was happening at any

particular moment of the experience. The researcher may prompt the participant

with questions to direct their attention to different aspects of their

experience, for example: “What were you doing here?,” “Did you have any

thoughts when you looked up?” or “What did it feel like when you

went in?”; or to direct their attention to a specific behavior observed in

the recording: “You seem to be looking around a little more here, was there

something that caught your eye?”

2.4.1.2. Micro-phenomenology

Unlike

cued-recall, micro-phenomenological interview (Petitmengin

et al., 2009) did not use visual prompts to assist the participant with

re-immersion, and was administered by an interviewer trained in the method. The

interview started with a short practice interview not related to the virtual

experience (discussing a moment from the recent weekend) to give an opportunity

for the participant to get familiarized with the method and what is expected

from them. Then the interviewer asked the participant to identify one or a few

moments in their experience that stood out to them and invited them to focus on

each moment at a time. The interviewer than lead the participant through the

process of the re-evocation of that moment directing their attention to

different sensory and temporary dimensions of their experience.

2.4.2. Implicit Attitudes

We used

the same Implicit Association Test (IAT) for assessing one's connection to

Nature as in Schultz

et al. (2004). This measure is used to measure interconnectedness—the

component of the Overview Effect. This test asks participants to categorize

words in one of the two categories by pressing “E” or “I” key on a computer

with left and right index finger, respectively. In the test trials the

categories are appearing together creating either a congruent or non-congruent

pair (Figure

3). The results are based on response reaction time and accuracy for

congruent and non-congruent category pairs. The categories were Self vs. Other

and Nature vs. Build with 7 blocks of trials.

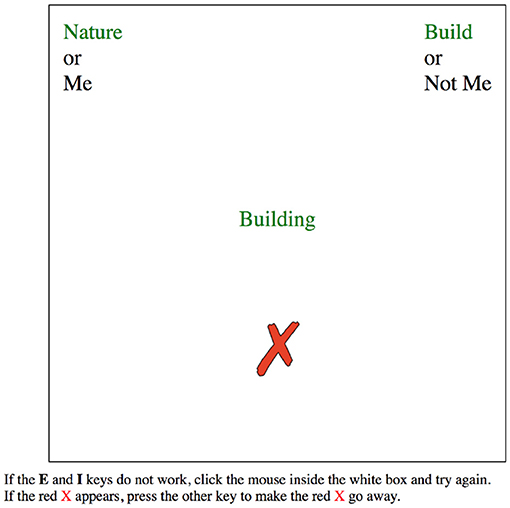

FIGURE 3

Figure

3. The Implicit Association Test (IAT) screen with congruent

categories pairing and inaccurate response.

2.4.3. Piloerection: Goosebumps and Shivers

Piloerection

observed in a form of goosebump or shivers can be used as a physiological

marker of awe (Benedek

and Kaernbach, 2011; Quesnel

and Riecke, 2017). A “goosebump camera” (see Figure

4) was placed on participant's arm to record a video of their skin during

the experience. The researcher helped participant to put on the camera and

adjusted the focal distance from the camera to the skin for the best clarity of

image. Video recording from the camera was manually synchronized with the screen

recording of participant's experience for future alignment.

FIGURE 4

Figure

4. Custom made set-up of a wearable camera for recording a video

of participant's skin for identifying goosebumps and shivers.

2.5. Analyses

2.5.1. Interview Thematic Analyses

The

interviews were transcribed and analyzed in NVivo. Even though some of the data

was collected with micro-phenomenological interviews, we didn't perform a

micro-phenomenological analyses for this study, but analyzed all of the

interviews through the same phenomenolgical method. First, two researchers

independently went through the transcripts, identified meaning units and

combined them into higher level themes. The two researchers then compared and

discussed the themes, they have identified, to agree upon one set of themes.

Then the researcher went back to NVivo and proceeded with coding. To minimize

the researcher's bias in interpreting the data we used “bracketing” and a

bottom-up coding approach similar to interpretive phenomenology analyses (Smith

and Osborn, 2004) and looked for themes that naturally emerge from the data

instead of coding for the specific themes of interest. We present the summary

of the distribution of all themes, however, in the interest of space, we will

only report in detail on the most prominent and relevant themes.

2.5.2. Implicit Association Test

We

calculated IAT effect D scores of strength of association based on a standard

algorithm for IAT (Wittenbrink

and Schwarz, 2007). D scores have a possible range of -2 to +2. According

to standard conventions we identified the strength of connection in accordance

with the following break points: “slight” - (0.15 ≤ |D| < 0.35),

“moderate” - (0.35 ≤ |D| < 0.65); and “strong” - (0.65 ≤ |D|).

2.5.3. Goosebumps and Shivers

The

video recordings from goosebumps camera were independently manually coded by

two researchers to identify moments of goosebumps or shivers. Moments of

goosebumps are visually evident from hairs erecting, with the appearance of

raised bumps on the skin. Shivers have less prominent raised bumps, but they

are evident from micro-movements of muscles under the skin that visually look

like a wave lifting the hairs up slightly.

The

first two section of the results report on quantitative data, and the following

discuss the interview data. First, we present the interview data based on the

thematic analyses. After, we present the analyses of categories of emotions

related to awe based on a hermeneutical analyses reported in Gallagher

et al. (2015) and compare it to the results observed in Quesnel

and Riecke (2018), that used Google Earth VR.

3.1. Implicit Association

Test

Mean D

score across all participants was 0.46 (SD = 0.54), which indicates

a moderate strength of positive connection between Self and Nature. Nine

participants had a moderate to strong positive connection (M =

0.78, SD = 0.23), two participants had slight or moderate

negative connection (M = −0.39, SD = 0.25), and

two participants had neutral scores (M = −0.11, SD =

0.0015).

To give

context to our observed results, we compared our results to to D-scores

obtained on the same IAT test by Schultz

and Tabanico (2007), who observed an average 0.40 score between 60

undergraduate psychology students and 0.45 between 121 park visitors in

California, we can speculate that possibly the effect of our virtual experience

is similar to the effect of walking in the park in terms of one's implicit

connection with nature. However, the sample sizes and the context in which the

measures were conducted were widely different, and therefor a strong comparison

is not possible.

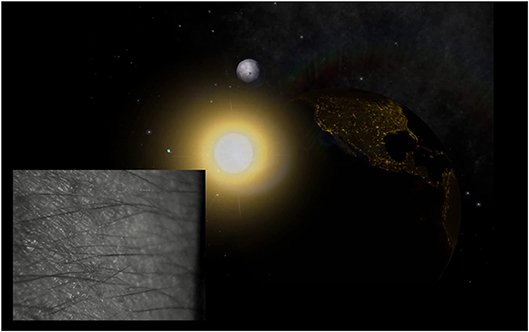

3.2. Shivers

In this

study we observed one moment of shivers in one participant, when the

participant was observing the sun revealing behind the dark Earth. The Figure

5 illustrates the moment when the shivers occurred.

FIGURE 5

Figure

5. The moment of shivers: aligned recording from the goosebump

camera and screen recording from the HMD showing the Earth scene with the sun

appearing from behind it.

3.2.1. Thematic Interview Analyses

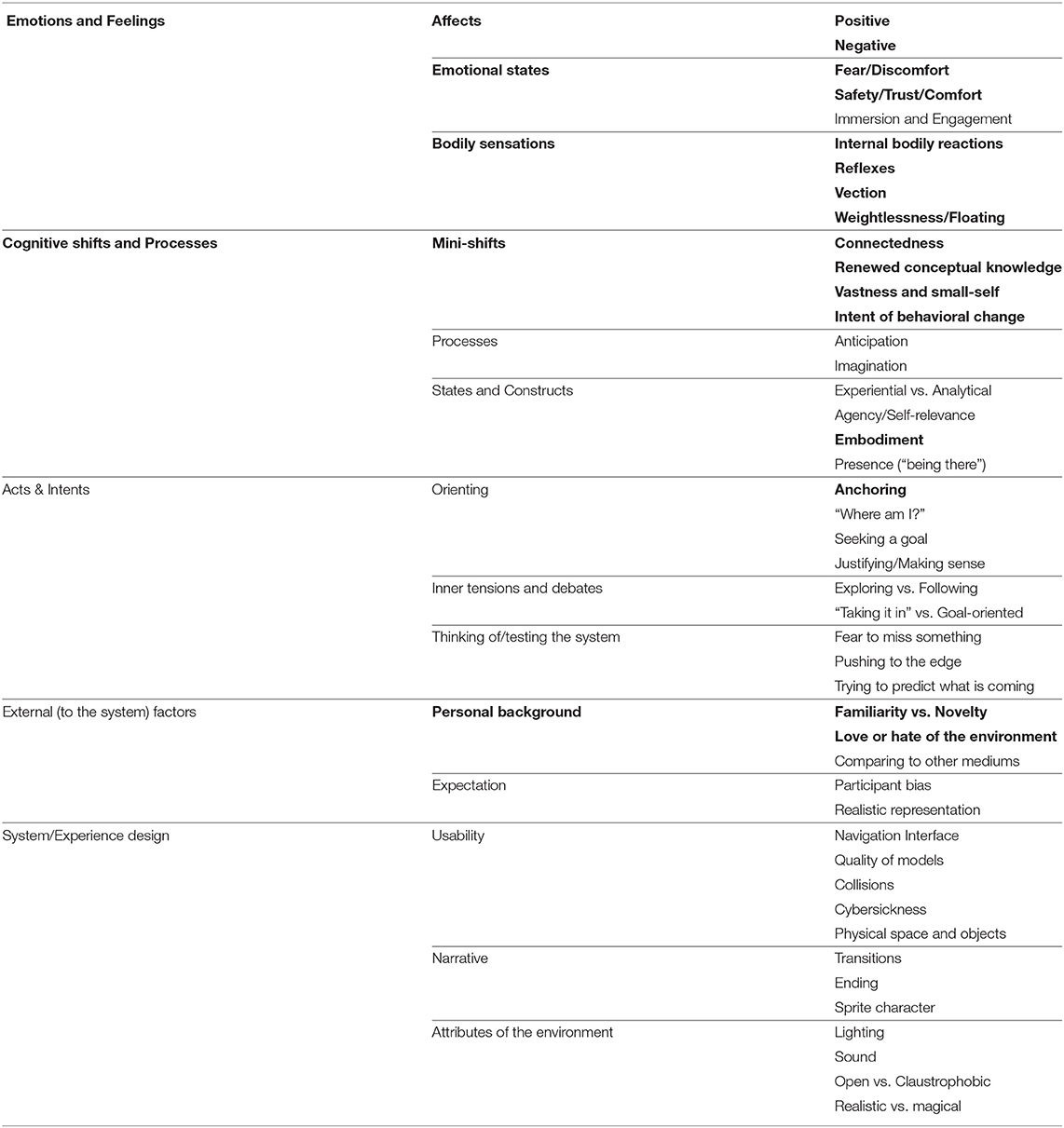

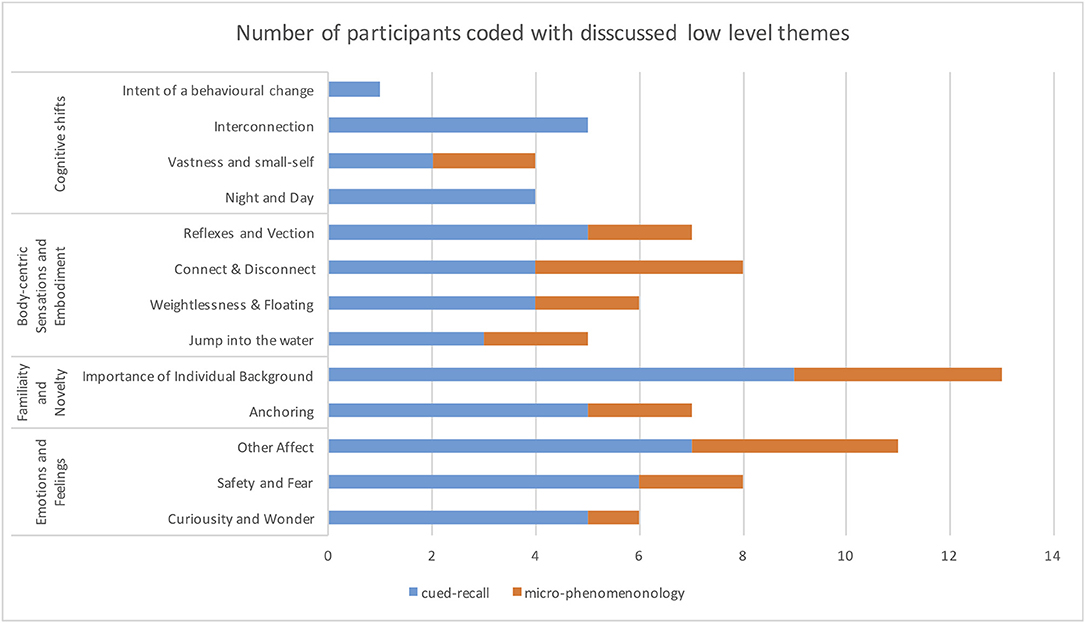

Table

1 summarizes all the themes observed and coded in the data. We are

setting the usability and design related comments aside, as they are outside of

the scope of this paper and will be reported separately. We are reporting on

the most prominent and relevant themes to this paper, specifically: emotions

and feelings, body-centric sensations and embodiment, familiarity and novelty

(role of the personal background) and cognitive mini-shifts. These themes are

highlighted in the Table

1 and their frequencies are summarized in Figure

6.

TABLE 1

Table 1.

Comprehensive summary of themes coded in the interview data, with the prominent

themes reported in this chapter bolded.

FIGURE 6

Figure

6. The number of participants (total = 13), that had statements

coded with themes reported in this paper.

3.2.2. Emotions and Feelings

3.2.2.1. Curiosity and wonder

After

“cool,” “interesting,” and “pretty,” “curiosity” was the most

frequent affect related word used by participants. Curiosity and wonder were

positive emotions driving participants' exploration behavior: “Another sense

of delight: Oh it's a lake! Not knowing what's gonna happen. Do I just look at

the lake? But when I break through the lake its quite a sense of wonder: oh,

that's quite lovely!” (P08). The properties of the environment,

specifically some level of mysteriousness or the “unknown-ness” of it, were

inspiring the curiosity: “I was just curious about the environment. The

environment felt deep. It reminded me the Truman show, where you have the

bubble that you can explore.” (P06), but at same time inducing some level

of fear: “It's really a lot of curiosity and I guess nervousness.”

(P11).

The

novelty and new perspectives were also contributing to curiosity: “I am

enjoying the curiosity. I guess I was more interested in looking at the Earth,

from this vantage point. I enjoyed looking at the space in reference to the

Earth” (P05).

3.2.2.2. Safety and fear

Most of

participants (N = 8) were distinguishing two states in relation to

the environment: comfortable and safe vs. uncomfortable and scary.

3.2.2.2.1. Safety. The majority (N =

11) considered the first environment, the forest, and especially the tent to be

safe and comforting: “the whole set up of the tent, and what I saw here…as a

tent was really, like, I felt safe. I felt the tent provided a safe starting

spot for me to start to going into the outside world.” (P01). When aiming

to achieve a transformative experience in VR, we believed that it was important

to have a safe starting point, to help participants trust the system to take

them on a potentially emotional journey and help them be more open to this

experience. If the medium is not allowing participants to feel comfortable

within it, they will likely be more resistant and closed-off from the

experience. The physical and the virtual tent appeared to successfully serve

that function for most participants. It was also important to conclude the experience

with a safe environment. Here participant describes the last transition and

coming back into the tent: “this again is much more familiar, I do this

every day kind of thing. It was comforting. Probably in a weird way one of the

most comforting parts” (P05). And since participants already developed some

connection and familiarity with that environment, it was even more likely to

elicit a sense of comfort: “Cozy. I felt like I was home, even though it's a

temporary home. Daylight, so it's more comforting” (P06).

3.2.2.2.2. Fear. Fear, was probably

one of the strongest and most interesting emotional reactions observed.

Participants reported being a little “scared,” “nervous,” “uncomfortable,” or

“anxious,” which was usually associated with the jump into or descend in the

water, or, in a few cases, with walking through the dark forest. Both, the act

of jumping of a height and the descend into the deep water was uncomfortable

for some participants: “Then I looked down and I see everything is dark, so

for me it was .. I don't know how to explain.. it was just uncomfortable a

little bit.. somewhere you are in the water and everything is dark and you are

going down” (P09). This was also the transition into the lake where

the locomotion was more restricted than in the forest, that increased the level

of fear:“I know that if I jump into the lake I can get out as fast as I can,

and it's up to me, but I felt like jumping in with the weights attached to your

ankle—I am not in control of this situation and it doesn't make me feel

comfortable. I am being lead. I don't want to be lead” (P06). This

also relates to the role of the sense of agency in the environment, the loss of

which was often undermining participant's enjoyment.

There

were many strong bodily reactions to the jump and descend into the lake in the

VE, that was surprising and in some way profound for the participants: “I

felt a shock. It felt like I was choked. That surprised me. It was not just

like “Oh that was kind of weird,” I did feel like someone poked me or

something. I felt an actual zap to myself, a tension, that I wasn't expecting.” (P05)

The

strategies participants used to cope with this fear were: (1) dissociate from

the experience and bring yourself to the analytical level: “Mentally

overwrote back that this is just the experience.” (P06), (2) find a

comforting point of reference: “There is fish, which is a comforting

reference point in this black void. Trying to follow the light.” (P05), and

(3) just wait for it to pass: “I noticed myself clutching my hands. I am not

comfortable, I am just going to wait it out until it goes away” (P06).

3.2.2.3. Other affects

A

distribution of positive and negative valence affects were observed. Negative

affects were coming through two main sources: (1) usability issues were causing

frustration and inability to explore something of interest was causing

disappointment and (2) some parts of the environment were causing nervousness,

anxiety or fear, discussed in the sections below. Positive affects could be

categorized into the following groups: excitement, inner peace and appreciation

of beauty.

3.2.2.3.1. Excitement. Participants were

describing their experience as “fun,” “exciting,” “wow.” These affects were

often related to the visual and audio attributes of the environment: “The

sun was really exciting, because it is bright. There is music attached to it

obviously, other than just my vision, it was also creating that kind of

excitement. Bright and exciting” (P04); or to an interest and anticipation:

“When I first looked around I was kind of hoping I would get to go in there,

an when I saw that you can, there was a bit of excitement that I can go and

explore the forest around. During that time I was actually looking around a

lot. It was kind of immersive, it was fun” (P03).

Another

aspect of the experience that seemed to elicit excitement was the vertical

dimension, which is opening a novel perspective. Often, when looking up: “I

kept looking up and thinking how far down am I. It was pretty neat, it was cool”

(P13) or down: “So I didn't look down that much, but when I did, it was kind

of fun and kind of scarier than looking elsewhere” (P04) participants would

describe themselves being more engaged and excited. While the lack of vertical

dimension of gaze direction they considered to be the evidence of low

engagement: “I wasn't inclined to look up and down, I was looking more left

and right, more like if you are in museum or something and you're kinda looking

around” (P03).

3.2.2.3.2. Inner peace. Participants

reported feeling relaxed and peaceful. The soundtrack appeared to significantly

contribute to it: “It was very peaceful and soundtrack was nice and reminded

me of nature and being in the forest” (P08), which was also helping with

coping with anxiety from jumping into the lake: “The sound was calming, just

seeing fish and seeing the opening above me made me feel a little more relaxed”

(P09).

3.2.2.3.3. Appreciation of beauty.

Participants described the beauty of the elements of the experience and how it

made them feel delighted or appreciative. Both, the mystical and novel

environments like the nebula: “There is something about it that I can't

define. Because I know these are asteroids and that's probably a planet of some

sort but then the fog is like ‘Awww.’” (P01) and familiar natural beauty of

the forest: “I like lakes, particularly because I can see the mountains and

the sky behind it, so I wanted to look closer <…> I

liked it, I can just sit there and look” (P06), as well as the beauty of

the image of our planet: “It's just visually really striking. And again,

familiar because you've seen images like that. And, the contrast between the

dark and the light is really nice.” (P12)—were all eliciting moments of

appreciation and delight in participants.

3.2.3. Familiarity and Novelty

3.2.3.1. Relation to emotions

The

feeling of safety or fear as well as curiosity and wonder seem to often be

related to the feelings of familiarity and novelty. The first environment of a

campsite in a forest was familiar to most participants, and associated with

positive emotions, which let them feel comfortable going into the environment.

“It's a very familiar place. It's a tent, and there's a bonfire. There might

be other people there. I chose to come here. I chose to be here and setup a

tent and sleep in a tent” (P01). Moreover, throughout the virtual

experience, participants will form new connections with elements of the

environment and use them to bring themselves back to the state of comfort in

the parts that felt scary to them: “…for my one comfort: ‘here is the light,

follow the light, here are some fish, I am being sort of acclimatized

here’—that time helped” (P05)

While

usually familiar environments were providing a sense of comfort, for other

participants, they appeared less engaging. Contrary, novel environments were

stimulating curiosity, wonder and excitement. Here a participant is at the end

of the lake scene: “It felt like ‘oh cool!’—Its not something you would

normally be able to see, where is in the previous environment—I have gone

camping before, so I get it. But here I am thinking this is cool, its really

creative, really beautiful to see the stars through the water”(P08). For

some participants it was easier to accept and get immersed in more novel

environments, they wouldn't have had a concept for, while having a compelling

familiar environment seemed more challenging:

It is neat to explore a perspective on the world that you would

have none of <…> Where is when anything that is too

familiar, because I am so in-tune with how I walk and how that feels, so you

have that disconnect <…> Where in space—I have no

context for that. So okay, this is how I would float in space, fair enough, I

have no other way of knowing it. (P02)

3.2.3.2. Anchoring

The act

of cognitive anchoring to a familiar place was quite prominent, and it was not

only used as a coping mechanism against anxiety and discomfort provoking

environments, but also to orient oneself: “I saw the sun and recognized it,

and quickly after that I saw the Earth, so there was a relation there—I knew

where I was for the first time in the experience. Not that I haven't been in a

tent before, that was quite familiar. But there I for sure knew where I was.” (P04)

and to connect with the environment in a more meaningful way: “This is kinda

of an interesting angle of North America and South America. I have a colleague,

who is working in Columbia right now, so I am trying …I am putting real people

I know” (P05).

3.2.3.3. Importance of individual variables

and background

We were

surprised to observe polarly different responses from our participants within

such a fairly simple experience, with a fairly consisted journey. Each of the

stages and transitions in the experience has produced opposing responses from

love to hate and from relaxation and peacefulness to excitement or fear. This

distribution of reactions has stressed the significance of participant's

individual background.

The

lake environment was the most striking example of opposing experiences

participants were having and its relation to their background. One participant

describes her delight in that stage: “I just love the water, and so going

into the water was quite delightful. Happiness, familiarity, for me not too

calm, but connectedness to nature in that way” (P08). While another

participant had a very different reaction to the same environment: “A little

worried. I don't like deep water. A little anxious. Okay, we got to go over to

the lake, I hope we stay above it” (P06). Transition into the lake as well,

which was reported to be one of the most memorable moments by most

participants, elicited opposing reaction depending on personal background: an

uncomfortable anticipation and anxiety by one participant: “coming down the

little ledge to go in the water. that was kind of .. I was a little bit

hesitant before, because I don't normally like jumping into the water from

height. Or jumping from height in general. That feeling scares me a little bit” (P09),

while another participant had a positive anticipation and excitement coming up

to that transitions: “I realized that okay, I am going down to the water, so

perfect. This is great. <…> I was a little stoked, cause

thats the direction where I wanted to go <…> I was a

little bit timed here: Am I supposed to jump in here? <…> then

I went for it” (P11), this participant later mentioned being a

cliff-jumper.

Another

important influence on the experience was coming from the video-games

experience, that participants had, that was both helping them with navigation:

“I have a little bit of a gaming background so I am sort of very comfortable

with this first-person movement through virtual space” (P13), and setting

up an expectation to have a goal: “ it reminded me of old video games

where there is like a mission or something, I wouldn't necessarily do that

mission and I would end up going off somewhere else” (P10).

3.2.4. Body-Centric Sensations and Embodiment

3.2.4.1. Jump into the water

As

discussed in the section on safety and fear, the transition into the water

environment, that was inviting participants to jump into the lake, was inducing

strong reactions in participants' bodies. They were describing clutching their

hands, tensing up their muscles and holding their breath: “all your muscles

constrict, or contract, so it's almost like you are trying to hold yourself

tight, so when you get that cold, you can release it once you hit the water”

(P02). This tension was often followed by a release and relaxation, when

“hitting the water”: “the body just kind of tense up, and you just kind of

…just kind of muscles release …As soon as I got in the water” (P09).

3.2.4.2. Weightlessness

Interestingly,

that feeling of release might have facilitated the feeling of floating or

weightlessness. Here a participant describes the moment when that release

happened:

That's weird, because, on the ground, up to that transition, I

am super conscious of how I am sitting on a chair, and that kind of leaning

forward is feeling a little awkward…But in that second I didn't feel the…And

that's what I kind of loved too, is how, I had no idea you could reproduce

that, give that sense that you are weightless, suddenly I wasn't conscious of

my body pressing into the Earth. (P02)

For a

different participant a similar moment of release leading to the sense of

weightlessness happened in the transition into the space: “When I was in the

water I felt like I was not in control and I was weighted down, like if I had

weights around my ankles, where is when I was transitioning into the night sky

it felt like the opposite: the weights are off the ankles, you are weightless” (P06).

This participant was afraid of the water environment, and even though that

transition into space produced less internal bodily responses for most

participants than the transition into water, the psychological release of

letting go of the fear still lead this participant to experience the illusion

of weightlessness.

It was

interesting to observe that 6 participants have mentioned floating or the

feeling of weightlessness. It might not have been a strong bodily feeling for

everyone, but it is encouraging to see that even with a simple hands-free

leaning-based interface through a design of the storyline and the visuals, we

were able to elicit some level of the feeling of weightlessness without

submersing participants in a flotation tank [which would be a more literal

induction of the feeling of weightlessness, for instance, planned by SpaceVR

for 2018 Burning Man festival (Bonasio,

2018)].

3.2.4.3. Connect and disconnect between mind

and body

Imaginative

immersion in combination with sensory immersion (Ermi

and Mäyrä, 2005) when achieved successfully creates a condition in which

participants experience a disconnect between their mind and body. Participants

discuss these moments of disconnect, and having their perceptions overridden by

their imagination as the optimal moments of their experience: “It was a bit

more of the imagination and just like the feeling of being in warm water and

submerging and yet not worrying about the panic of not being able to breath,

and just something about that, that I quite liked. And maybe it's because I

didn't feel this [points at different parts of his body], right?” (P02).

While the moments, in which the conflict between the physical body position and

the virtual position became apparent, lead to frustration and disappointment: “You

start unpacking, okay, so you have this goggles, the audio here, and my arms

and legs just feel static and crossed, how does that connect? Because that

feels weird, when you come back to your body and then realize that it is a

stagnate lump going through this [points at where HMD would have

been]” (P02). It would be interesting to investigate how this

connect/disconnect transitions are being triggered. In case of this

participant, he had this desired disconnect during the lake stage that was

initiated by a visceral jump into the lake and then “something broke the

spell” (P02) when transition into the space happened. For him, the

transition into the space came as a surprise and did not make sense. For a

different participant, the conflict was the result of not having an avatar

representation in the VE: “I felt a bit disconnected from my body, because

when I look down I don't see my body, and usually its there, obviously”

(P04).

3.2.4.4. Reflexes and vection

Vection

(an illusion of self-motion) and reflexes are often perceived as an indicator

of how immersive and “believable” the experience was by participants.

For

example, a participant describes descending down in the lake: “I see the

sparkles, <…> I realized that they are kind of like

surrounding me, that's when I really got the sense of the descent down. The

closest I can compare it to is when you are going down a roller coaster, but it

wasn't that intense, it was more calm kind of feeling” (P03) and then

going into space: “As soon as the movement started, it kind of again felt a

bit more immersive, the floating feeling came back again” (P03). The lack

of self-motion illusion for some participants in space combined with restricted

locomotion might have also contributed to some of them feeling as if they are

watching a movie instead of participating.

Sometimes,

participants would also report having a reflex in reaction to an event in the

VE: for example, when the sun appeared, a participant was surprised and

reported: “I am pretty sure I jumped.” (P05) while another participant

mentioned: “I found the sun pretty bright, almost wanted to put my hand up.

But yeah, this is neat.” (P10). While putting the hand up to protect one's

eyes wouldn't have worked with an HMD, a different participant adopted her

reflexes from diving to the VR equipment: “because I'm a diver I felt like

I'm descending, there was one point were I adjusted my face but it's a bit like

adjusting your regulator.” (P14). This type of behavior could potentially

indicate how “real” the experience was for the participants at that moment.

This

“realness” and “being there” of the experience, that is indicated by

multidimensional responses, including your internal body feelings and actions,

are likely an important precursor to the possibility of transformative experience

that could lead to cognitive shifts. For instance “presence,” which is often

described as the feeling of “realness” or “being there” in a virtual experience

was shown to correlate with a stronger effect of the virtual experience on the

following real-world behavior (Fox

et al., 2009; Rosenberg

et al., 2013).

3.2.5. Cognitive Mini-Shifts

As the

ultimate goal of this project is to evaluate if VR experiences can be designed

to elicit positive cognitive shifts similar to the Overview Effect and other

awe-inspiring transformative experiences, we were excited (and a little

surprised) to see some indication of some minor cognitive shifts voluntarily

described in the interviews. Participants themselves were also intrigued by the

shift in perspective resulted from their experience, even when the shift was in

the perception of seemingly simple concepts:

I kinda compared that sort of spatial environment that I was in

with all of the representations of space that we get used to, which is a very

2D item, the solar system prospective. And that difference, that being in it,

and that way how it altered my sense of that relational space of one celestial

body to another, that was really cool actually how it changed something in my

mind slightly. (P13)

3.2.5.1. Day and night

Four

participants found the concept of day and night happening at the same time on

different sides of the globe, that was observable in the experience when

traveling around the Earth, very interesting. Even though they are

intellectually familiar with this idea, seeing it from the first person

perspective was a somewhat “eye-opening” experience. Participant reflects on

her mental process of coming to that realization:

To realize that it is so easy to look at something through one

lens, but when, if you are exposed to it in a different way, then something

that was so familiar to you …can give you such a different perspective.

Something as simple as that sun is not shinning on the other side of the half

of the world, means its night time, and it's so simple. And I studied, moons,

and tides and sunrises and sunsets, but never thought about it quite so simply:

that sun is shining on one side but not the other side. (P08)

3.2.5.2. Vastness

Vastness

can be better described as part of the perceptual experience that could lead to

a cognitive shift (rather than a shift in itself), but as it is considered to

be the precursor for the experience of awe (Keltner

and Haidt, 2003) and cognitive shift of perspective (Gaggioli,

2016), they are closely related. A participant, who works at an aquarium

described:

I remember thinking that the Pacific ocean is so big and for a

while I thought that I am not seeing things correctly. Which is funny, because

I <…> know that its huge. But it was so vast!

And to see it in that perspective was what was very unique for me. <…> It

was impressive and gave me another perspective on something that I see and

think about everyday. (P04)

This

admiration of vastness is also often related to the realization of how small

each individual human is on the scale of the whole world. Here a participant

describes his thoughts when orbiting around Earth: “I was really hoping to

see maybe that sparkle of the civilization, some kind of movement, some kind of

glimmer, to denote my …what's the word …like the size of people, how small

compare to where I am” (P03).

3.2.5.3. Interconnection

Overview

Effect and other transcendent and awe-inspiring experiences have all in common

the cognitive shift leading to a realization of interconnectedness of life. In

our data there were a number of instances that could indicate this realization

of wholeness of the world: “transition from the bottom of the water into the

space scape and that sort of the initial moment when you look at it

holistically and you see …everything is involved in it” (P11). But the most

striking was the observation of the participant when traveling around the

Earth:

There has been so many natural disasters lately with the

hurricanes, fires and all of that. When you see at a global level, the

connection between things that are otherwise separate because of the political

things…When you see as a whole—its just like, well, its just one planet. When

you go around and see that Brazil is so close to Florida, you know politically

things are so far away… (P06)

This

realization of interconnectedness can then lead to behavioral changes, where in

case of the Overview Effect, astronauts feel the need for everyone to unite

together to protect our planet and its inhabitants (White,

2014).

3.2.5.4. Intent of a behavioral change

In our

data there were two comments from one participant that could suggest an intent

for a change in behavior, that could be triggered by the feeling of

interconnectedness. Firstly, on a personal level, she was inspired to learn

more about other people and countries she may not know enough about: “I

don't know much about south America, so it was interesting to look at it when I

can see all other distracting places I know more about. I thought I should

learn more about it” (P06). This could be related to the aspect of

perspective shift related to brining cultures together by developing an

understanding of other cultures [similar to what astronauts describe (Gallagher

et al., 2015)]. Secondly, on a more global level, she had the urge to

communicate this view of interconnectedness to more people:

Just need for people to figure out the environmental sciences,

because its effecting everybody, but these are the artificial lines that seemed

to be so unhelpful. I was thinking from the educators perspective. What a

disservice it is to see a map as flat: things look so much further apart than

they actually are. And that need—if we are going to problem solve bigger

things, how this flat political map is just not going to get us there. (P06)

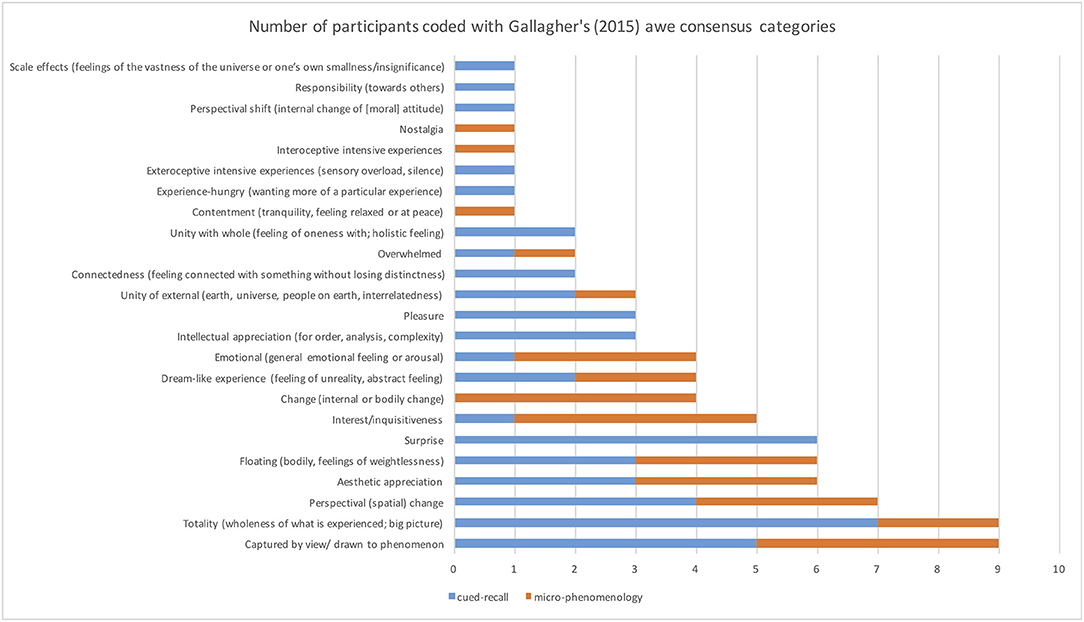

3.3. Gallagher's

Hermeneutic Analyses of Awe

Gallagher

et al. (2015) undertook syntactical followed by hermeneutic analysis

of astronauts' awe experiences based on 51 texts by 45 astronauts. From the

analysis, Gallagher et al., generated 34 consensus categories of awe. They

allow researchers to determine whether in experimental studies, participants

have experience of awe and Overview Effect. Here (Figure

7), we count the frequency of statements made by our participants that fit

into the awe consensus categories. The categories that were not observed in our

data and not included in the graph are: sublime, poetic expression, peace

(conceptual thought about), inspired, home (feeling of being at home),

fulfillment, floating in void (not related to weightlessness), elation,

disorientation.

FIGURE 7

Figure

7. The number of participants, that had statements coded with

hermeneutics analyses of categories of awe (Gallagher

et al., 2015).

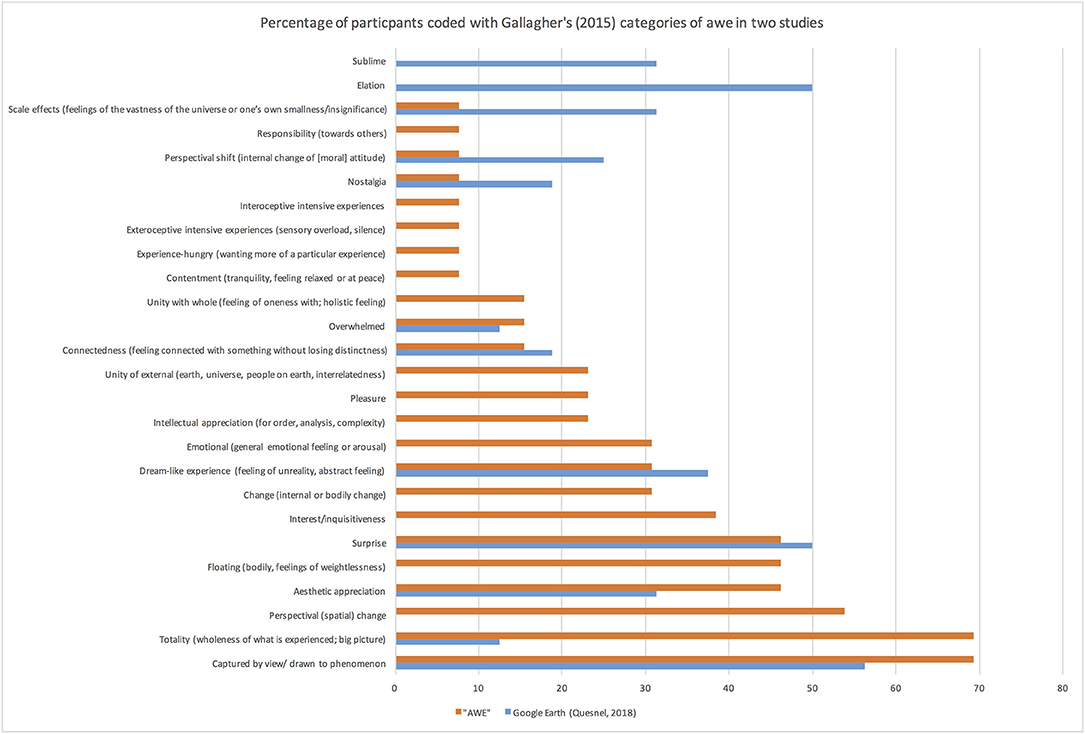

We can

compare the results of this study to the study by Quesnel

and Riecke (2018), that had 16 participants traveling through Google Earth

VR, whose interviews were coded with the same categories of awe based on Gallagher

et al. (2015). Figure

8 shows the comparison of the frequencies of participants coded with

the awe categories between these two studies. The “AWE” experience

was able to elicit more responses of totality, spatial perspective shifts,

sensation of floating and inquisitiveness, while the Google Earth experience

was better at eliciting feelings of sublime and elation. We can speculate that

the sensation of floating and inquisitiveness were elicited as a result of the

narrative arc of the “AWE” experience, that wasn't a part of the

Google Earth experience used in Quesnel

and Riecke (2018). Totality and the spatial perspective shifts observed in

our data are likely related to the “AWE” experience presenting the

Earth from a more distant perspective than Google Earth VR allows. While the

lack of sublime and elation responses in our study could be explained by the

difference of the quality of the Earth models that we had in “AWE” and

in the Google Earth VR.

FIGURE 8

Figure

8. The percentage of participants, that had statements coded with

hermeneutics analyses of categories of awe (Gallagher

et al., 2015) in current study and Quesnel

and Riecke (2018).

Gallagher

et al. (2015) did not report on the number of participants coded with

a certain theme, but rather the total frequencies of codes (within 19

interviews). However, since the lengths and types of interview procedures were

different between the current and Gallagher

et al. (2015) studies, we can not make a precise comparison based on

these counts. Still, in their data the most frequent categories were

perspective shift (moral,internal), contentment, interest/inquisitiveness,

scale effect, and significant sensory experiences, which only partially

intersects with our data, as these categories, even though present, were not as

prominent in our data. The study design was fairly different between our

studies: Gallagher

et al. (2015) study used a spaceflight simulation, designed to be

realistic, that was presented through the screens of cockpit/window as opposed

to an HMD. As their study was a more literal simulation of a spaceflight than “AWE,” it

is possible that their participants were more inclined to think about what they

know about astronauts' experiences, so it is possible that some of these

thoughts were introduced externally based on associations rather than emerged

from the properties of the experience.

4.1. Relating to the

Overview Effect

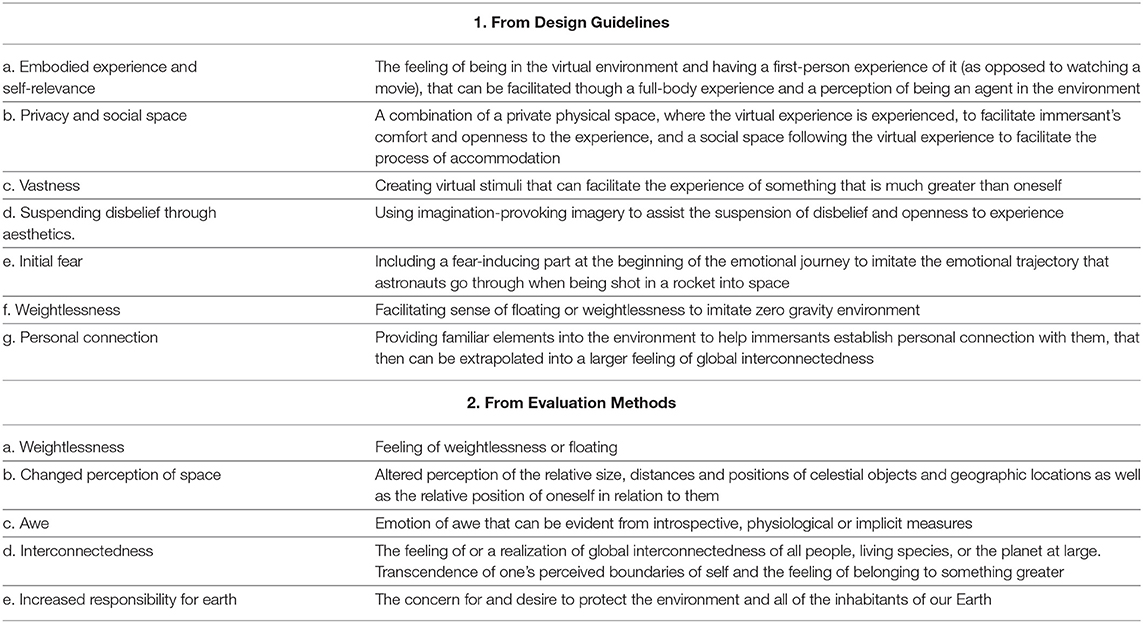

Stepanova

et al. (2019) analyzed existing records and research on the Overview

Effect and derived design guidelines and evaluation methods for virtual

experiences aiming to elicit the Overview Effect or an extent of it. Comparing

the themes that emerged from our data and the guidelines outlined in Stepanova

et al. (2019), we identify an intersection in the themes outlined in Table

2.

TABLE 2

Table 2.

Selected design and evaluation guidelines for design of the virtual experience

of the Overview Effect from Stepanova

et al. (2019).

From

the evaluation guidelines we were pleased to observe some mini-shifts reported

by participants, that would indicate each one of the 2b-2e themes. Even though

we only observed a few instances of each, it was still very encouraging,

considering that cognitive shifts are not easy to achieve, and it was still an

early prototype of “AWE.” From the design guidelines, the most

strong and interesting intersection was in the privacy, initial fear,

weightlessness and personal connection components.

4.1.1. Privacy and Social Space

Even

though participants were not using the term “private,” from their discussion of

felt safety and comfort we can speculate that “AWE” was able to

achieve the goal set out by the “privacy” design guideline—creating a safe

space for participants to feel comfortable to have a transformative experience.

The social space guideline was aiming to assist with the process of

accommodation that is a necessary component of a transformative experience

following a witnessing of an awe-inspiring vista. Even though only one

participant explicitly discussed it, but he reflected on how going through the

process of the interview was valuable to help him unpack his experience and

understand it on a deeper level than if he was just asked a few questions.

Hence, we believe that the interviews, especially the microphenomenological

method, were able to provide the social space and the conversation that could

facilitate the process of accommodation.

4.1.2. Initial Fear

The

precursors for the Overview Effect are hard to separate from components of a

spaceflight, but the initial moment of fear naturally experienced when being

shot in a rocket into space, is, quite possibly, an important stage in the

progression of the experience (White,

2014). However, few people have personal experiences associated with

rockets, and as such, jumping into water is a more visceral experience for most

and therefore, when part of VR, has a potential to induce stronger response,

which we indeed observed. However, we were surprised by the strength, length

and frequency of fear experiences, as we were only intending for the jump into

the lake to be a moment inducing hesitation and requiring participants to take

the leap of faith. The personal background of participants shaped their

experience of descending through water to be more fearful than we anticipated

during the design process.

4.1.3. Weightlessness

The

connection of feeling of weightlessness and Overview Effect is also unknown as

the records of them are inseparable: it might be essential or not relevant (White,

2014). As the sense of weightlessness on Earth is logistically challenging

to achieve in combination with VR, we were not aiming to replicate it as a part

of the experience. It was insightful to observe that several participants did

have a feeling of floating or weightlessness, and informed us how the narrative

of the experience can facilitate the induction of this sensation.

4.1.4. Personal Connection

In at

least some astronaut's descriptions the feeling of connectedness starts small

from the personal connection to a familiar location, and then extends from

there to the rest of the world. It was interesting to see in our data how

prominent the concept of familiarity was—10/13 participants were discussing it

(with no targeted prompts from interviewers). Two participants also described

how, when orbiting around the Earth, they were picking out familiar locations

to establish connection to them, much like the astronauts describe. The virtual

travel to a familiar place in Google Earth was also powerful at eliciting awe

in the study by Quesnel

and Riecke (2018).

The

other three design guidelines (embodied experience and self-relevancy,

vastness, suspending disbelief through aesthetics) were not as evident in our

data. Even though there are some indications of self-relevancy, for a lot of

participants it was significantly reduced as a result of restricted locomotion

in the last parts of the experience. While perceived vastness was mentioned

three times, this is a fairly low frequency for an experience aiming to elicit

awe (Keltner

and Haidt, 2003). Suspending disbelief through aesthetics was only

partially successful, as a lot of participants were still expecting an accurate

representation of the real world inside the VE and were thrown off by any

observable conflicts. Despite the clearly magical creature, sprite, and the

lake portal into space, some participant's sense of immersion was broken by

seeing jellyfish in fresh water, some trees appearing too tropical for the

local biosphere or the tent seeming too large for one person. Evidently having

magical elements in the narrative wasn't enough for suspending participant's

disbelief, especially when they were very familiar with a specific environment

(e.g., the jellyfish comment was made by participant working at the aquarium).

It might be important to set up the right expectations from before the VR

experience starts by adding a narrative to why participants enter the tent for

going into the VR experience to prepare them for the virtual story.

Overall,

even though the “AWE” experience did not follow all of the

guidelines outlined in Stepanova

et al. (2019), it was able to achieve some indications of each one of the

core components of the overview effect: awe, increased connectedness, increased

responsibility for the environment. The latter being indicated only once by a

participant discussing the need for everyone to unite together to develop a

better understanding of the weather systems as it is effecting everyone.

While awe is a complex emotion, it is hard to make definite

claims as to how much awe did our participants experience: their interviews

indicate a number of components of awe identified by Gallagher

et al. (2015) specifically in the context of the Overview Effect.

However, the physiological measure of piloerection (Benedek

and Kaernbach, 2011) revealed only one instance of awe in this study, which

is either the fault of the recording instrument or, more likely, the result of

the lack of intensity of awe that, even though experienced to some degree,

didn't trigger the physiological reaction.

Connectedness is also a difficult

cognitive construct to objectively measure, that we attempted with IAT. IAT

scores indicated a fairly strong connection between Self and Nature, however

these results are challenging to interpret, as we don't have a baseline for our

Vancouver population. We made the comparison with the data collected with the

same test (with identical items) in California, which could be an approximately

comparable population as they are both from the West Coast of North America,

although there still might be differences. Besides lack of baseline, we also

cannot know how much of the connectedness of nature and self was attributed to

the “AWE,” and how much of it was a personal trait. Implementing

IAT as a pre- and post-test measure could be a possible approach to tackling

this challenge (as in Peck

et al. (2013) in the context of racial bias), but as a reaction time

measure, IAT scores are greatly influenced by learning effects, and therefor

repeated tests become difficult to interpret as a measure of change. IAT is

very rarely implemented as a pre- and post-test measure, and as in Peck

et al. (2013) it requires inviting participants to visit the lab

multiple times, and still expects to observe a strong learning effect. The

qualitative data in our study, however, showed some promising indications of

moments of realization of interconnectedness.

As

traditionally the records of the overview effect are describing a moment during

the spaceflight, it is difficult to separate which components of a spaceflight

experience might be contributing to the Overview Effect and which ones are

unrelated. Until this relationship is clarified, we will have to target both

the components of the spaceflight and the Overview Effect experiences in VR

experience design. In our data we observed some indications of some components

of an experience of a spaceflight: change in perception of space and

weightlessness, but not the change of perception of time and silence. However,

we did not explicitly try to measure them.

4.2. Comparing to Other

VR Awe-Inspiring Experiences

Here,

we want to compare the current VR experience and study with other research

attempting to elicit awe and Overview Effect through the use of VR. This

comparison allows us to speculate about the role that the aspects of the VR

experiences and research tools had on the obtained results, thus informing

future research in this field. Chirico

et al. (2017), Chirico

et al. (2018a), and Chirico

et al. (2018b) have shown that an immersive experience of awe-inducing

stimuli were associated with a self-reported awe measured with a questionnaire,

however these studies used less interactive environment than in our study, and

did not perform an extensive qualitative analyses of how a participant's

experience in VR unfolded, what some key components of it were, and how they

relate to aspects of the virtual environments. Our study is most similar

to Gallagher

et al. (2015) and Quesnel

and Riecke (2018), who also used a VR experience of a spaceflight/orbiting

the Earth and collected qualitative interview data. They reported participants'

experiences of awe in those VEs across 34 consensus categories defined by Gallagher

et al. (2015) hermeneutic analysis, and compared participants' reports

of the virtual experience to real-life accounts from astronauts, with some

similarities identified. However, the environments used in both of these